I recently had the opportunity to chat with the co-founder of Avuá Cachaça, Peter Nevenglosky, about launching the brand and the growth of terroir-driven spirits. We cover everything from the time he unexpectedly met Sasha Petraske, to aging cachaça in an heirloom tapinhoã barrel.

Whether you’re new to cachaça or have tried your fair share, I guarantee you’ll learn a thing or two–I certainly did.

Nevenglosky’s path into booze may not have been entirely deliberate, but it was certainly logical. After receiving his MBA at NYU, Nevenglosky spent time as the brand manager for Dannon and then moved on to become the brand manager of Red Bull. Needless to say, he’s well-versed in what it takes to launch a brand.

PS – If you want to jump straight to some recipes, I’ve included a few at the end of this article!

Launching the Brand

Saliga: Before launching Avuá Cachaça, you were the brand manager for Red Bull. How did that transition happen?

Nevenglosky: I had a passion for products. I particularly had several bartender friends and a lot of interest in spirits: the history, the origins, the flavor profiles and why they were there. I wasn’t in the industry per se but spent a bunch of time in New York City engaging the different bars, trying new things, and getting to know the community.

Places like Milk & Honey and Employees Only that were really creating a new universe and opening peoples’ minds to… well, first, establishing the classics but then introducing new products into the mix that nobody had ever really considered.

Saliga: And that’s how you were introduced to cachaça?

Nevenglosky: I was first exposed to cachaça at a little Brazilian botequim, Miss Favela, in Brooklyn. In the back of my mind I was asking, how have I never heard of this before? We now have some products that we sell there, which is kind of cool.

I subsequently ended up traveling down to Brazil on vacation and tried some amazing stuff. Was just blown away by the range. There are actually over five thousand documented producers of the stuff.

I brought back a couple of bottles, one of which was aged and we now call Amburana, which is one of our signatures. It’s a native wood. And my bartender friends were just kind of losing their mind about it. Something they were never exposed to, and we saw an opportunity with the usage of it. So we just started exploring.

I went back down there and spent more time, tasted hundreds of cachaças, and ended up sneaking fifty back in a suitcase. Forty-seven of those made it–a pretty good ratio.

The Impact of Meeting Sasha Petraske

Saliga: How did you and your co-founder, Nate, get connected?

Nevenglosky: Nate lived in D.C. on the same block as me, so I got to know him on a personal level. We moved to New York right around the same time. He’d just finished law school. I was moving for business school and so we discovered New York together. We had complimentary skill sets and were looking for a new challenge, and found a passion.

I don’t think there was any real vision for spirits, let alone cachaça, but it has evolved from, “this is something that’s really interesting” and “there’s really not much of it here”. We built an idea of what we could represent, as being a lens on how unique this product is and how good it can be, which was differentiated from what was going on at the time with Leblon and the focus on the caipirinha only and a lot of the industrial stuff.

We found a little pocket of a niche idea and we had a bunch of people who knew a lot more than we do who were excited about it. So we started building the brand proposition, which is rooted in 50s and 60s Rio. We wanted to represent something a bit different.

Then we had the fortune of meeting Sasha Petraske and not even recognizing who he was at the time.

We were in a coffee shop in the West Village interviewing somebody, maybe nine months before Avuá launched. We had a mock-up bottle out, and this guy kept looking at the bottle. I stood up, started talking to him. He mentioned that he owned a few bars.

We ended up tasting the Amburana, and he liked it. We met up at Little Branch, blind-tasted the Prata in a caipirinha against what he had there. He loved it and said, “When you get enough stuff, let me know”. That ended up being us previewing the brand at the construction zone that was the new Milk & Honey, where he moved it to for about a year before they ended up selling the building. And then, he unfortunately passed.

It was a classic New York moment of somebody who was, incredibly respected, had a brilliant palate, and for whatever reason, liked what we were doing and put a stamp on it for us. That was the start.

Saliga: At what point did you realize who you had spoken with?

Nevenglosky: I talked to him for 20 minutes. He wrote down his email as *****@gmail.com. I was like, “Holy shit!”. Meanwhile, Nate who is also in the interview is just giving me this dirty look like, “What are you doing? We’re in the middle of an interview”. I was like, “Don’t worry about it, man.” Petraske wasn’t a very socially active person. He was great one-on-one, fairly misunderstood.

Oddly enough, we were talking about his bars with our advisory board when I created some makeshift target lists. I put a couple of them on there and they’re like, “Forget it. Never going to happen. You’ll never get to him.” And probably could’ve never happened any other way, honestly.

Saliga: As far as the selection process goes, you mentioned trying several hundred cachaças. How small-scale are these operations? Were some simply in unlabeled bottles?

Nevenglosky: It is a mixed bag. We directly reached out to some people to try and set things up. I just showed up at other places. Some of them on the more sophisticated side. Of course, they were all very craft, very pot-distilled, estate-grown cane for the most part.

Some were family traditions passed down and they had a decent business in Brazil and others were just kind of, “We only sell within a five-mile radius, we make our labels and we’re pretty off the grid.” So it’s a wide disparity.

Saliga: So were you acting like an interested tourist or did you let them know what your objective was?

Nevenglosky: I did let them know what we were doing because a lot of it was not just the quality of the cachaça, it was how it would be to work with them. Having a vision of doing that, it’s like, do they get what you’re doing? Are they interested in that kind of business and exporting and building something in concert?

Aging in Unique Woods

Saliga: Going back to what you said and I saw it was part of the mission statement, ceasing to think of cachaça as a “one-trick caipirinha pony” and emphasizing it being terroir-driven. I found that to be the most interesting aspect when I first heard about your brand and I saw the different woods they’re aged in. At what point did you discover the range of finishing methods and how did you select the ones use in the product line?

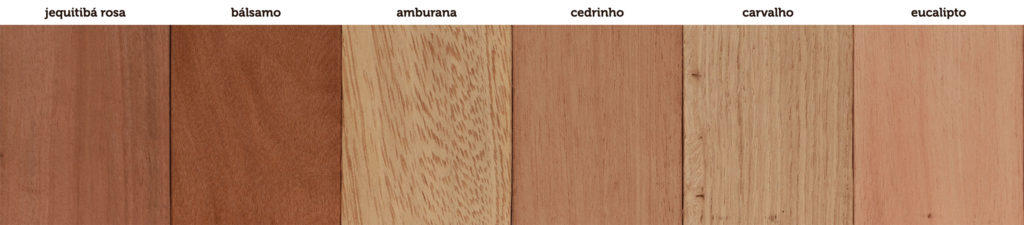

Nevenglosky: The first exposure to it wasn’t till I got down there. I knew there was some aging that went on, but I had no idea how deep it went. There are 30 plus woods that cachaça’s aged in. So it started with French oak, and that was just production. Predominantly happened on the coast, primarily in an area called Paraty, which is in Rio state in the South. They would take the cachaça in on ox carts to Minas Gerais which was a rich mining area. So we’re talking 1700-1800s. They’d put it in oak barrels just because that’s what they had to store things. It would take months to get in and they realized that it had a positive impact on flavor.

They then started experimenting with native woods, just in a very Brazilian way. It’s like the anti-French is how I describe it. The French are like, “there’s only one way to do this.” And Brazilians, they’re like, “Oh, we got all this stuff. Screw it. Let’s see what happens.” Some of the first stuff I tasted, our producer was already working with French oak and Amburana. Her Amburana is phenomenal. It’s a huge part of our business. It is an amazing cocktail ingredient.

We launched with Prata and Amburana in New York in the first year, and then we started adding subsequently. So French oak was kind of the no-brainer. We want people to understand what this is like in oak. It’s a much more familiar profile. I think it helps people understand the other woods too.

After that, we started looking at what else was out there in the tradition that we want to get involved in? The first thing that we realized is that she had some old barrels of a wood, well one in particular, of a wood called tapinhoã, which is an obscure wood. I’ve never found a bottle of it in any other range. I’ve only seen evidence of it on the Internet. So, her father used this barrel. We basically broke it down, sanded it, and then rebuilt it.

We did a little bit of quick testing to see how it worked with the juice on some chips and then realized it was going to be great. That was our third one. Really beautiful, really layered. It’s lovely to sip. It evolves in the glass. It’s something totally different.

From there, we started investing in other barrels, things that she had not worked with before. So it’s kind of a mutual alignment process of tasting other things in the market, knowing that our base wood is going to perform differently than other base woods, different woods, even subspecies of woods, et cetera.

The next one we released was Jequitibá Rosa, with Rosewood. It’s a thousand-liter barrel, very small production. Very light. A lot of things that are subtle undertones. And then, thereafter, we invested in some Bálsamo barrels, which is another prominent wood down there. It’s our newest release. Really unique. Again, very different profiles. But it’s amazing going from the Prata base and to all these different woods and how they perform and what they yield in terms of cocktail usage. They’re all so different from each other.

Resinous Woods and Coopers

Saliga: Going back to those vintage barrels, the tapinhoã… that was a previously used barrel that you sanded down, so that means that you have no more access to that wood. It’s kind of a one-off? Can you sand it down and then fire the barrel again?

Nevenglosky: We don’t fire any of the native wood barrels. We call them resinous woods. The oil and the sap of the wood interact with the spirit.

Saliga: So there’s so much already there you don’t have to draw it out as much?

Nevenglosky: Every wood interacts differently. I think it’s a shame that everything’s so oak-driven because it doesn’t help you understand the characteristics and how they interact with each other.

Saliga: I was impressed by reading that you have actual coopers that you use. I realized you’re very artisan-driven.

Nevenglosky: There are traveling coopers that move around. It’s an art form there. A lot of these barrels that are three, five thousand liters, they’re vertically oriented. They’re built and maintained on-site. They’re heavy and large and not very movable. It’s a bit of a pain because it’s like, “Oh, you could probably come out in three months. We’ll see.” You’re definitely on their time, not your own time of business need as opposed to, all right, he’s ready to come out.

Sugarcane in Avuá Cachaça

Saliga: On to the sugar cane. I saw that you use four different types of sugarcane? [Link: More info on their sugarcane.]

Nevenglosky: It’s actually five now.

Saliga: And it’s always the same five because the Prata is your base?

Nevenglosky: Right.

Saliga: What does that process look like? Are you working with the university to make some of the hybrids? Or do they already have the hybrids and you source from them?

Nevenglosky: That’s a good question. There are thousands of types of sugarcane. Occasionally, there are brands, even in Agricole, that will do one single type of cane. But usually, it’s some kind of blend. Our cane is oriented to best perform in the altitude and climate that we’re in. Our producer is a third-generation female distiller. Her grandfather bought the farm. There was already cachaça being produced there, but we don’t know a lot about it before then.

When it was passed down to her from her father she took the traditional methods, but then she went to study at university and look to the future of where this distillation can go maximize that. It was trying different hybrids that were developed at this university. Hybridizing different cane types that were already there to find the best kind of quality and yield for different regions.

Sustainability

Saliga: As far as the parallels to mezcal production and sustainability, that’s a big topic lately… What does that look like for Avuá, for both the sugarcane and the wood?

Nevenglosky: With the sugarcane itself, we’re lucky in the sense that it’s an annual crop. We will plant on the same fields for several years in a row, maybe five or so. And then we’ll let it come back before we circle back on it. It’s all estate grown. So, everything is owned by the family that they grow on. They know the land extremely well.

In terms of sustainability on woods, there are a few things. One is that the government dictates what woods are acceptable for use and not. There are some pretty tight restrictions. Whenever we source woods, we source them from a recognized producer under a note de fiscale, so it’s kind of an approved harvest from the government.

Then what we do is plant trees on top of what we use. So, something like a 10:1 ratio where we’re replanting on the farm.

However, anything like Tapinhoã, for example, is prohibited from use. This is just a reused barrel. Essentially, we’re using barrels that we’re getting decades of use out of, that are either repositioned barrels in the case of things that are endangered or just bought from the market with clear origin and proper harvesting.

The Heirloom Tapinhoã Barrel

Saliga: I’m still hung up on that heirloom barrel. That’s just such an interesting concept. I don’t recall any spirits that have had a story like that with an old barrel that has been in a family and reused.

Nevenglosky: It’s awesome. It looks like a Frankenbarrel. It’s all beat up. We did a project with MGM resorts where we got four large hardy cognac barrels down to the distillery and we took tapinhoã, Amburana, oak, and our-still strength 90-proof, and we’re finishing them in these barrels. The first one to come out is going to be the tapinhoã, and it’s one of the best things we’ve ever made. So there’s going to be a very small amount of that if it makes it out into the universe, but I would encourage you to find a bottle if you can once we put it out there. It’s really special stuff.

Saliga: I saw that you have a special connection to the Pan Am cocktail because Sasha came up with that one, right?

Nevenglosky: Yeah, one of his guys came up with it. We did a little cocktail competition internally because he found the Amburana so interesting, but didn’t necessarily know exactly how to use it. So we held a competition and that was one of the drinks that came out, which is super simple but complex and delicious.

How to Drink Avuá Cachaça

Saliga: If you had to pick one to drink neat. Obviously, that’s a personal preference, but what is your go-to? Or would you drink it on a rock?

Nevenglosky: I like drinking it neat. Tapinhoã, we’ve talked a lot about it. I love it. Amburana is amazing too. Really unique. Lovely to sip as well.

Plans for New Products and the Potential Impact of Tariffs

Saliga: Branching out towards the broader portfolio of Drifter Spirits, you have aquavit as well. Are there any plans to add any other spirits?

Nevenglosky: There are.

Our whole vision is to scour the world for historically relevant, underrepresented spirits for the modern bar.

We think there are a lot of interesting things out there that have a specific geographic identity that is beautiful. We’re always exploring. What we do have coming for sure is a falernum under the Avuá name, which will be Amburana in still-strength based. That should be this summer of 2020. It’s higher in proof, around 23%, really expressive.

We got a couple of things coming. Hopefully. There’s a little bit of an unknown around tariffs and things like that, that are slowing down the process of a couple of other things we’re looking to bring in.

Saliga: I didn’t realize that was affecting the spirits market as much.

Nevenglosky: It’s unclear, but any European modifier or spirit is currently up for that potential according to the way it’s written. So literally Grey Goose, for example. Also Campari. It’s unclear where it’s going to go, but it’s certainly kind of putting a hold on any real plans because when you’re working on craft products the margins aren’t huge. Bigger companies are probably better able to figure some of these things out than smaller companies are.

Top Takeaways

Saliga: If you gave readers one takeaway, what would it be?

Nevenglosky: What I would encourage is for people to take some of these products, especially the aged ones, play with them in classics, see how they operate. Don’t be afraid to experiment. These are spirits, including aquavit as well, that weren’t around when all the classic cocktails were written up. They can apply in incredible ways in tiki and classics.

I think people get a little bit too hung up on exact specs. I’d say just try good products, be open-minded, experiment with them, see how they work for you.

I’m excited for people like you to be talking about these categories and these products, and I’m excited for people to start getting out of the kind of just super traditional approach to drinking and making cocktails at home. Access to amazing spirits from around the world is increasing by the day. It’s an exciting time to be doing these things.

The Humble Conclusion

I’m looking forward to cachaça gaining popularity, but am curious if it will rise to the same level that mezcal has in recent years. I think that mezcal’s rise can be partially attributed to the familiarity of tequila. And while rum and cachaça are basically cousins, I think that the loosely regulated and broad range of styles of rums keeps some from making the logical connection that both rum and cachaça are sugarcane-based spirits.

However, one thing that cachaça certainly has going for it is that it is an artisanal terroir-driven spirit. I believe that once people begin to better understand this category, the rich history, and the diversity that comes from the use of regional woods, it will gain popularity. Whether it’s sipped neat or incorporated into a classic cocktail, it’s a spirit that deserves more recognition. People gravitate towards narratives, and Avuá’s narrative is one that captivates both the palate and attention better than any mass-produced industrial cachaça ever could.

Recipes

Caipirinha

Ingredients

- 2 oz. cachaça

- ½ lime (quartered)

- 1-2 tsp. superfine sugar

Instructions

- Muddle quartered lime and sugar in a cocktail shaker.

- Add cachaça and ice, then shake until chilled.

- Pour, unstrained, into a chilled glass.

Italian in Rio

Ingredients

- 1¼ oz. Avuá Cachaça Prata

- 1 oz. Aperol

- 1 oz. Dolin dry vermouth

- 1 dash celery bitters

Instructions

- Combine ingredients in a mixing glass with ice and stir until chilled.

- Strain into a chilled cocktail glass.

Pan Am

Ingredients

- 2 oz. Avuá Cachaça Amburana

- ½ oz. triple sec

- ¼ oz. dry vermouth

- orange twist (garnish)

Instructions

- Combine ingredients in a mixing glass with ice and stir until chilled.

- Strain into a chilled cocktail glass and garnish with expressed orange twist.

The Oscar

Ingredients

- 2 oz. Avuá Cachaça Amburana

- 1 oz. amaro (Averna is a good choice)

- 1 oz. orgeat

Instructions

- Combine ingedients in a cocktial shaker with ice and shake until chilled.

- Strain into a rocks glass over a large cube.

- Garnish with an expressed lemon peel.

Additional Resources:

- Avuá-Cachaça – Official Site

- Avuá-Cachaça – Instagram

- Avuá-Cachaça – Twitter

- Drifter Spirits

- Where to Buy (If you’re in the service industry in Oklahoma, order via Republic.)

- Avuá-Cachaça – Simple Cocktail Book [PDF]

- Avuá-Cachaça – Complete Cocktail Book [PDF]

- Dornas Havana – Official Site (Avuá-Cachaça’s cooper)

- Dornas Havana – Instagram

- Miss Favela

Disclaimer: I received product samples from Avuá Cachaça with the agreement that the article or review that I wrote would be my honest opinion, whether positive or negative.

![Avuá Cachaça – An Interview with the Co-Founder [Plus Recipes]](https://www.thehumblegarnish.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Avuá-Cachaça-Amburana-and-Prata_01-2.jpg)